| City/Town: • Miami |

| Location Class: • Commercial |

| Built: • 1926 | Abandoned: • c. 2013 |

| Historic Designation: • National Register of Historic Places |

| Status: • Abandoned |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Table of Contents

History of the Dade Commonwealth Building

Located in downtown Miami, across from the Shoreland Arcade, the Dade Commonwealth Building was constructed in 1926 and originally known as the Meyer-Kiser Building, named for the building’s largest tenant, the Meyer-Kiser Banking Company. Its original design and construction featured seventeen stories and was once one of the tallest in Miami and Dade County.

The Florida Land Boom

The prior years were significant for the City of Miami, as they marked the peak of a remarkable real estate boom. During this period, Miami underwent a dramatic transformation from a quiet, small town on the shores of Biscayne Bay into a bustling metropolis often referred to as the “Magic City.” This transformation was characterized by the construction of skyscrapers and substantial real estate profits.

The real estate boom in Miami began to gain momentum in the spring of 1923 when the city saw a notable increase in the issuance of building permits. This growth continued to escalate, with the volume of building permits reaching an astonishing one million dollars per month. In August 1923, the city even reached a remarkable milestone by issuing four million dollars worth of building permits in a single month.

As a result of this rapid development, downtown Miami became a massive construction site. In 1925, the city removed the ten-story height restriction from its building code, paving the way for the construction of even taller structures. These skyscrapers adopted the latest construction technology, the steel frame, which had become popular after the Chicago Fire. This innovation allowed for the construction of taller buildings with non-load-bearing walls, thus giving rise to what we commonly refer to as “skyscrapers.”

In terms of architectural style, the “Commercial Style” was favored for these new skyscrapers. This architectural style was developed by the Chicago School and typically featured a three-part composition consisting of a base, main body, and projecting cornice. While Miami’s buildings may not have been direct replicas of the Chicago School’s work, they did incorporate the steel frame structural system and the three-part classical composition, aligning with the architectural trends of the time.

Meyer-Kiser Bank

The Meyer-Kiser Bank was established in 1895 in a small office at 306 Indiana Trust Building which is no longer extant. The Indianapolis News wrote, “Back in 1895, a new firm opened its doors for business at 306 Indiana Trust Building in a single office, with no clerks, no telephone, a second-hand desk, and unlimited ambition. Physical and financial resources were few and scanty, but there was the nucleus of fine and honorable personal reputations to build on, confidence, worlds of good will from many friends, integrity, and a dominant will to succeed. “Meyer & Kiser” it said on the door, Real Estate, Insurance, Loans and Investments.” The firm was Sol Meyer and Sol. S. Kiser.“

Solomon Meyer was born in 1866, and his first job was as a telegraph operator with the Western Union Telegraph Company. He drifted from this into working for the Pennsylvania Railroad in Richmond, Indiana, and worked his way up to the position of chief clerk in the superintendent’s office. Being a young man, he believed he didn’t have a chance to grow in such a large corporation, so he resigned from his position in 1893. He went into the business of selling insurance, real estate, and bonds for two years before partnering with his cousin Solomon S. Kiser and establishing the Meyer-Kiser Corporation. It wasn’t until 1906 that Meyer-Kiser Bank was founded with Meyer as its president.

The firm quickly grew and within a year, its office was moved to the Pembroke Arcade, considered Indianapolis’ first shopping mall. Between 1916 and 1924, Meyer-Kiser occupied a 4-story structure before outgrowing that building as well. Meyer-Kiser financed a 13-story building overlooking the old Pembroke Arcade and just west of their previous building which was completed in 1926. The building still stands today at 130 East Washington Street in Indianapolis, but it’s unrecognizable from its original construction.

The Meyer-Kiser Bank was also a pioneering institution in the early 20th century that actively sought to attract employed or self-employed women as clients under the category of “businesswomen.” They launched a campaign to promote their services to this demographic, and a key figure in this campaign was Blessing Fisher, a longtime employee.

Blessing Fisher served as an assistant to Meyer and had been with the bank since its opening. Her extensive experience in banking, particularly in legal affairs, made her a valuable asset to the institution. The bank recognized her expertise and her gender, and they decided to put her in charge of serving the bank’s women clientele. As part of their marketing efforts, the bank used streetcar cards featuring Blessing Fisher’s image along with text that conveyed their commitment to assisting women who were wage earners.

Miami’s Meyer-Kiser Building

In 1909, attorney Frank B. Shutts arrived from Indiana to serve as a federal receiver for the failed Fort Dallas National Bank of Miami. Shutts, who had a good law practice in Indiana, found Miami’s heat unbearable and had intended to straighten out the bank’s affairs and return home. Instead, he was hired by Henry Flagler who offered him a $7,500-a-year retainer which was more money than Shutts had ever earned in a year. Within a few years, he would become one of Miami’s most powerful civic leaders.

After marrying his secretary Agnes J. John Shutts and permanently moving to Miami in 1910, Shutts borrowed money from Flager and founded The Miami Herald. He also ignited Carl Fisher’s interest in developing Miami Beach who Meyer spoke highly of saying that Fisher was “a subject worthy of a statue” and that “He ranks, in my opinion, as high as Henry M. Flagler.” Shutts also headed the Miami Telephone Company, Miami’s first telephone company, and was instrumental in the construction of the Tamiami Trail and the construction of the Dixie Highway.

In the 1920s, Shutts persuaded Meyer to open a bank branch in Miami. Meyer would finance real estate developers Jerry Galatis and Samuel Locke Highleyman’s new $1,500,000 building and agreed to be its major tenant. Due to his experiences with tornadoes back in Indiana, Meyer insisted that the building be covered with wind insurance which later proved to be an excellent decision.

When the Meyer-Kiser Building was erected, it was considered one of the most robust and impressive edifices in downtown Miami, standing tall at a height of seventeen stories. Regarded as “another imposing monument to Miami’s progress and permanency,” it held the distinction of being among the earliest steel-frame structures equipped with an elevator. The building opened on January 2, 1926.

On September 18, 1926, less than a year after the Meyer-Kiser opened to the public, a massive hurricane hit Miami and marked the end of the era’s land boom. At least 114 people lost their lives as a result of the hurricane, and thousands of residents were left homeless. The hurricane’s winds, which reached speeds of 132 miles per hour, along with a tidal surge, caused extensive damage to the city. The waterfront was often described as being “flattened.” The storm passed west through Miami before moving out into the Gulf of Mexico, continuing its destructive path, striking other areas, including Pensacola, the region north of New Orleans, and eventually reaching Texas.

Following the storm, the Meyer-Kiser Building was described “the most visible victim of a killer hurricane that shattered boom time Miami.” The Miami News wrote that “The twisted steel superstructure was one of the most appalling sights in a graveyard of ruined architectural masterpieces. Miami’s citizens could no longer boast of a skyline that resembled Manhattan. They could, however, compare it to San Francisco—after the quake.” Many witnesses stated that the building swayed back and forth reminiscent of the “Charleston” dance. Police closed the street below fearing the building would collapse.

Thankfully for Meyer’s forward-thinking, the building was said to be the only building that carried wind insurance and owners Galatis and Highleyman received the largest damage payment in Florida history at the time in the amount of $675,000. With the certainty that it would be a long time before Miami’s fortunes would recover, the owners decided not to repair the entire building and instead to remove the upper ten floors, bringing the building down to just seven stories tall. Their reasoning for the decision was that tenants would be scarce for a long time to come and so, it made no sense to put a large amount of money into the building.

Meyer-Kiser Bank moved elsewhere until its failure in the stock market crash of 1929. The building retained the name but with Kennedy and Ely Insurance Company as its prime tenant. During the intense Labor Day Hurricane of 1935, the Meyer-Kiser Building easily withstood the storm, but Kennedy and Elyn decided it was time to move on.

In 1936, the American National Bank moved into the building’s ground floor and with that, the building was renamed to the “American Bank Building.” In November 1938, the building acquired the Miami Public Library as a tenant which occupied crowded, insufficient space on the third floor. The library expanded into the fourth floor in 1949 and moved out on July 1, 1951, when a permanent home for the library collection was constructed in Bayfront Park.

The American National Bank was absorbed by First National Bank in 1944, leaving the ground floor without a tenant. The Dade-Commonwealth Title and Abstract Company decided to move from their offices on the fifth and sixth floors of the building, down into the bottom floor. The name was once again changed, this time to the “Dade Commonwealth Building.”

Martin Luther Hampton, Architect

The Meyer-Kiser Building was designed by architect Martin Luther Hampton, a little-known but prominent architect in South Florida. Born on August 3, 1890, in Laurens County, South Carolina, he settled in Miami in 1914 after studying at Columbia University in New York. He received his architectural license in Jacksonville in 1916 and began working in the architectural firm of August Geiger. Hampton became well known having painted a thirty-two by forty-four-inch bird’s eye view of Miami which was purchased by the Chamber of Commerce to be used in advertising.

Before he opened his own architectural firm in 1917, Hampton worked for George Edgar Merrick, the planner and builder of the city of Coral Gables, designing a cottage at 937 Coral Way for Merrick and his wife Eunice Peacock.

After serving in World War I, Hampton was hired by architect Addison Mizner to design interiors and supervise details for Mizner’s own projects in Palm Beach.

A 2003 report conducted by Ellen J. Uguccioni and Sarah E. Eaton states that in 1921, Merrick sent “his design team” for Coral Gables to Europe to study the architecture to be used in Coral Gables. This team consisted of Denman Fink, Merrick’s uncle, artistic advisor for the City of Coral Gables and designer of the Venetian Pool and Coral Gables City Hall; H. George Fink Sr., Merrick’s cousin and once called “The Henry Ford of Architecture” by the New York Herald Tribune; Leonard B. Schultze, a New York-based architect whose later works included the Biltmore Hotel, the Breakers Hotel, and the Freedom Tower. Hampton was among this group of influential individuals.

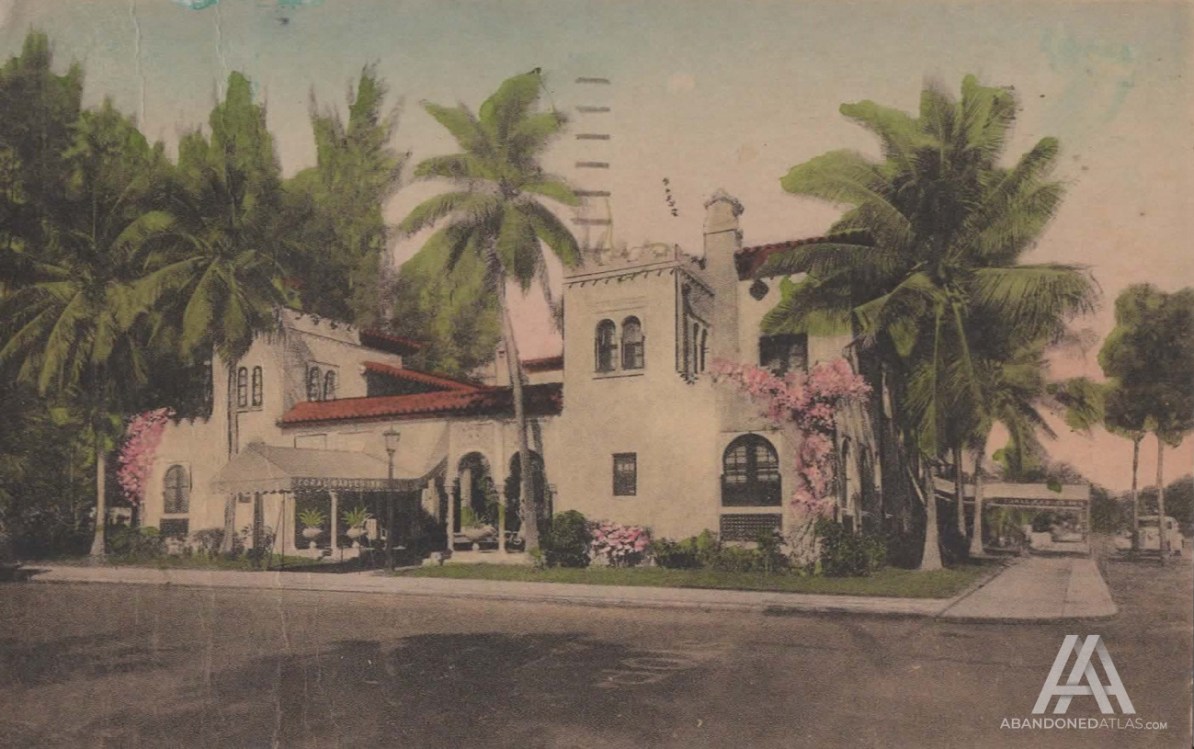

In 1922, Hampton designed the Variety Hotel at 1700 Alton Road in Miami Beach and the Coral Gables Inn at 303 Minorca Avenue in Coral Gables, demolished in 1972. The Inn was constructed for George Merrick and was the first hotel in Coral Gables, used to house prospective buyers in the new development. It was U-shaped around an open courtyard, with the open end of the U crossed by a tracery-work arcade that rested on slender columns, and covered by a red tile roof. Elsewhere the roofline is crenellated. Reminiscent of a Spanish tavern, the lobby featured an open fireplace and was described as a Mediterranean Revival masterpiece. These designs would feature heavily in his later works such as the Country Club of Coral Gables (1923) and the Casa Loma Hotel (1924).

Possibly inspired by his work on the Country Club of Coral Gables, Joseph Wesley Young, developer and founder of Hollywood, Florida, hired Hampton in 1923 to design what would become known as the Hollywood Golf and Country Club, later demolished in 1961. Hampton’s other works in Hollywood include The Great Southern Hotel (1924), demolished and rebuilt in 1921; the second Young Company Office and Administration Building (1924), and the Hollywood Beach Casino (1925).

Among these huge projects and ventures, his other works include the residence of Walter Collins Hardesty, Sr. (1924), Colony Hotel & Cabaña Club (1926), the Glenn Curtiss Mansion (1926), the Osceola Apartment Hotel (1926), and of course, the Meyer-Kiser Building. In his later years, he experimented with Art Deco, designing the Ocean Spray Hotel and the Royal Polo Hotel.

Architecture

In regards to the building’s design, The Miami News wrote, “The entire motif of the architecture of the bank faithfully follows out the Spanish atmosphere and design, even the grating of the tellers’ windows and the wrought iron fence dividing the main banking room from the safe deposit vaults, being done in a dull copper finish, giving them an old, corroded appearance.

Henry Behrens of Indianapolis, who executed the mural decorations, and Martin Hampton of Martin L. Hampton associates, who originated the architectural motif, have carried their work through to the last detail, giving to Miami one of the most beautiful and finished banking quarters in the south, in the belief of the bank’s officials.

On either side of the main banking room which is 125 by 50 feet, are the tellers’ cages, officers’ departments and quarters for the bond and security departments. These are divided from the center corridor by a series of nine arches on either side, finished with a special rough plaster, with ornate designs. Above and accessible from the main banking room, is the mezzanine floor, where will be located offices of four other departments. Over these two, floors will be centered the banking and other activities.”

National Register of Historic Places

The Meyer-Kiser Building, then known as the Dade Commonwealth Building, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 21, 1988. The description of the building reads:

The principal elevation fronts to the south and is only three bays wide. The side elevations contain 15 bays across their lengths, with each bay containing paired windows. The lower three floors of the principal elevation are characterized by four tall Composite columns dividing the elevation into three bays. The entrance to the building is comprised of an arch rising to a full two stories in height, capped by a cartouche with masonry molding. Flanking the entrance are two storefront windows containing fixed panes of glass. Atop the storefronts are triple windows set within the end bays. Over the entrance is a paired window, surrounded by an articulated masonry enframement. The four columns support an entablature located between the third and fourth floors. The entablature is plain except for stylized anthemion motifs found at its ends. There are four large eagle sculptures atop the entablature on the same vertical axis as the columns.

The building shaft is mostly brick and rises to a height of four stories. Paired windows are set within each bay, and very little decoration is found on the exterior wall. All the windows appear to be replacements, and many are awning-type windows set within metal frames. The windows on the lower three floors are casement-type, also set within metal frames.

The building’s roofline is characterized by an open loggia which spans the three bays of the principal elevation and extends back two bays along the sides. The loggia is delineated by a pierced parapet wall,’which once contained a decorative molded balustrade within its openings, and finals atop each bay division. Atop the parapet is a band with a classically-inspired molding which wraps itself around the loggia.

The building has undergone several modifications throughout its years of use so that no significant interior spaces remain. The offices were laid about a central corridor that extended from the elevator lobby in front of the building to the rear wall. Although its exterior has been slightly modified, the visual composition of the Meyer-Kiser Building does not significantly differ from the way it was rebuilt following the hurricane of 1926.“

Last Tenant and Abandonment

In 2011, the Dade Commonwealth Building was purchased by Jay V. Suarez, a partner with Titan Developers. The new developers renovated the building for about $5 million, with offices on the upper five floors and a nightclub on the first two floors. The nightclub was “The Bank Gallery and Lounge,” featuring four different event spaces: Gallery 139, a bright gallery space before the actual entrance to the nightclub; the Lotus Garden, an outdoor area; and the Capone Room, an upstairs lounge, named as such because the owners claimed Capone had used the bank in the past.

The Vault, the club’s VIP lounge, featured the original old Meyer-Kiser vault whose door weighs thirty-two tons, is sixteen inches thick, and has a layer of Don Steel, which is impervious to high-pressure fire torches. By 2013, the bar had closed down and the building soon followed.

Leave a reply